|

Orthopedic surgeon leads one-of-a-kind institute in sports

injury prevention research and advocacy efforts

by Robert Trace

ORTHOPEDICS TODAY associate editor

ANN

ARBOR, Mich.

David H. Janda, MD, has

a mission. He and his staff at the Institute for Preventative Sports

Medicine, located on the campus of St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor,

Mich., are waging an all-out effort to help coaches, parents, league officials

and players prevent sports injuries. David H. Janda, MD, has

a mission. He and his staff at the Institute for Preventative Sports

Medicine, located on the campus of St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor,

Mich., are waging an all-out effort to help coaches, parents, league officials

and players prevent sports injuries.

It also doesn't hurt that Janda

and his colleagues are helping take a bite out of national health care expenses

through their injury prevention efforts.

The institute conducts

seminars for the lay and medical communities on injury prevention, and is

currently the only health cost containment organization of its kind in North

America. Just one of the research team's findings provided keys to preventing a

proposed 1.7 million injuries annually in the United States, with a savings of

$2 billion in health care costs per year.

Injuries caused by sports,

falls, motor vehicle accidents and the unintentional discharge of firearms

remain the leading cause of death for individuals between the ages of one and

44, and these accidents cost the U.S. more than $133 billion each year in health

care costs, according to Janda, who is director of the institute. He is also an

orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine at Orthopaedic Surgery

Associates, a nine-physician orthopedic practice in Ann Arbor, Mich.

"Injury remains the most under-recognized major public health problem in this

country," he said, "and still we don't hear much about it in the media. The

public needs to understand that there are many potential solutions to this

problem."

He continues to field occasional inquiries from persons

wondering whether a proactive preventive approach would cut into an

orthopedist's business. "As an orthopedic surgeon, my job is to do what's best

for my patients, period," he responded. "There will always be patients who need

our specialized care. But I think one of the problems we've run into in this

country is not focusing enough on the prevention issue. Health care needs to be

made more affordable, and the way to help do that is by preventing need."

A labor of love

Janda volunteers 10-20 hours a week conducting research in

his lab at the institute, or touting the cost and health benefits of proper

sports injury prevention techniques to various groups.

Organized

recreational softball-which attracts over 40 million participants nationally

each year-is a particular area of interest for Janda, who claims 710/o of all

injuries from recreational softball and baseball result from sliding. While some

of these injuries are attributed to poor musculoskeletal conditioning, shoddy

sliding technique, and occasional alcohol consumption, the primary cause for

these foot and ankle injuries is a late decision to slide, he said.

A

baserunner's risk for injury is also determined in part by the type of base he

or she slides into, Janda acknowledged. Standard stationary bases are bolted to

a metal post that is sunk into concrete in the ground. "Breakaway" bases

utilizing a rubber mat fixed to the playing field by several low-profile rubber

grommets can be displaced at a fraction of the more than 3500 foot-pounds

required to dislodge a traditional stationary base. The breakaway bases, he

added, differ from bases which are secured to the mat via a magnetic or Velcro

strip, which can become ineffective when exposed to dirt or water.

Benefits of 'breakaways'

In their observations of more than 8500 players in a

softball league at the University of Michigan where half the games were played

on fields using stationary bases and the other half were played using breakaway

bases, Janda and his colleagues identified 45 sliding injuries involving

stationary bases. Only two sliding injuries occurred on the fields equipped with

breakaway bases. The total treatment costs to these 45 injured players came to

over $55,000, an average of more than $1220 per injury, excluding lost work time

and related costs, Janda said.

In the two injuries occurring on the fields using breakaway

bases, including a non-displaced medial malleolar ankle fracture and an ankle

sprain, the total medical costs for both injuries was only $700, or $350 per

injury. The ratio of injuries occurring on the stationary bases was 22.7 times

higher than that for the modified breakaway bases, Janda pointed out.

These findings were replicated in another phase of the

study, in which all fields were equipped with breakaway bases. Again, just two

injuries occurred in the more than 1000 games monitored, with the median costs

totaling only $400. This represents a reduction in injury occurrences (compared

with games played on stationary bases) of 98.70/o, Janda said. The

corresponding reduction in related medical treatment costs exceeded

990/o.

A congressional matter

Following Janda’s testimony before the House Appropriations

Committee on Labor, Health and Human Services, House officials developed federal

recommendations for the use of breakaway bases on recreational baseball and

softball fields in all federally operated facilities. These include all U.S.

military facilities worldwide, as well as federal correctional institutions.

Although Janda is advocating for mandatory use of breakaway

bases at both the amateur and professional baseball levels, he is pleased, for

now, that federal institutions are taking a proactive approach to prevention.

"According to the Pentagon, the No.1 reason for missed days in the military is

sports injuries," said Janda. "Hopefully, efforts like these will help eliminate

lost work time and the added costs of treatment and rehabilitation."

Still, a majority of Little League baseball fields and

office recreational softball leagues use the traditional stationary bases.

"It's a shame because we spent less than $1000 on this

series of studies, and according to the government, we found a way to save $2

billion in health care costs," Janda said. "when it comes to prevention, this is

not the exception; it is truly the rule. A very small outlaying of expenditures

can have a huge ramification on the prevention of injuries, as well as a huge

ramification in the prevention of health care costs."

Financial support Financial support

As a policy, the institute does not accept financial

contributions from the government or from sports product manufacturers in order

to best serve the public without a conflict of interest.

"Funding continues to be an ongoing area of contention for

us," he added. "Unfortunately, the insurance companies haven't shown much

interest in funding our projects, even though we have demonstrated, through

scientific research, the steps coaches and players can take to prevent injuries

and save medical costs."

Instead, the institute must rely on tax-deductible

contributions from individuals, foundations, corporations, and by grants from

public and private agencies to support its research and operations. The

institute's annual budget is approximately $200,000.

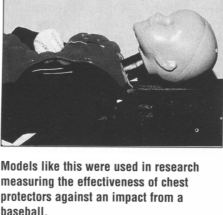

The institute's pursuit of better safety measures has not

been limited to breakaway bases, either Janda and his group recently studied the

fatalities of 34 children over the past 17 years who died after being struck in

the chest with a baseball during an organized baseball league game, causing

fatal arrhythmia.

The researchers compared the different chest protectors and

softer, heavier baseballs currently on the market. "what we found was that even

through many of the manufacturers made claims about how well their product

worked, they had no scientific data to back up them up," Janda said.

Working with auto

industry Working with auto

industry

Janda teamed with David Viano of General Motors, whose

company contributed crash test dummies and the Hybrid III Crash System-a

sophisticated computerized modeling structure used by the Justice Department for

ballistics testing and auto manufacturers for crash testing-to measure the force

of a fatal chest impact. The researchers then measured the potential for injury

resulting from the impact, even when the child was wearing a protective

device.

The researchers also measured the intensity of the impact

using traditional baseballs compared with softer, heavier baseballs claimed by

manufacturers to be safer for children. "We found the softer baseballs and the

chest protectors afforded no statistically significant benefit to the players,

and in some cases made the injuries worse," observed Janda, whose findings

appeared in the Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine.

He said the soft baseballs were too heavy to be effective.

"When we did our high-speed photographic work, we found the softer balls

actually stuck to the chest longer, posing a greater risk to damaging the

internal organs," Janda pointed out. "It enabled more energy and force to be

driven into the heart. The softer but larger-mass balls also pushed off with

greater force on the rebound, and we found the force of that 'double-hit' to be

additive."

Janda also reported the special chest protector for batters

and pitchers acted like a conductor, funneling the energy into the heart over a

shorter time period.

One important byproduct of the institute's research was the

introduction of softer, lighter baseballs. In a study to be published this

spring in the Journal of Trauma, Janda and colleagues detail their

findings on the effectiveness of these new lighter, softer baseballs.

Teach the fundamentals

The simplest, and often most efficacious preventive

measure, Janda believes, is teaching young athletes the fundamentals of their

sport. "We can't overemphasize the importance of instructing players on the

proper techniques of their sport, such as sliding in baseball or heading the

ball in soccer, so they can play safely."

For example, some children playing in leagues using the

softer, heavier baseballs are not instructed on how to get out of the way of a

pitch coming right at them. Many of these children are also assured by their

coaches that because the baseball is softer, the risk for injury is much less.

"Many of these children panic and step right into the pitch, and the ball hits

them in the chest," he said.

Janda became particularly disgruntled when Ann Brown,

director of the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission, recently

recommended widespread use of the softer, heavier baseballs, based on

information provided to her by the product manufacturers. "That kind of 'blind'

recommendation gives folks a false sense of security," Janda said. "It's like

claiming that, because a Cadillac and a Yugo are both cars, they are comparable

in terms of performance and safety."

Soccer

safety Soccer

safety

The institute is also researching the incidence of fatalities

among young soccer players who hit their head on the goal post, or had the goal

post topple over and fall on them.

After identifying the deaths of 18 children over a 13-year

period, Janda and his colleagues began work on a softer, lighter goal post. "It

took us about two years to design a goal post that was thinner and which didn't

alter the goal dimensions or the rebound of the ball, yet still protected the

athlete if he or she ran into it," he said. "We tested the goal post material

and it reduces the force incurred by a player's head or neck by over 600/o. We

also conducted a two-year field study on the effectiveness of the goal posts,

and of 14 player impacts with the post, there were no injuries."

In a related effort, Janda and colleagues observed soccer

coaches as they led their young players in heading drills. He recommends

children use a special helmet when first learning to head the ball.

"We would watch the coaches line the kids up; one child

would go first and head the ball a couple of times, and the coaches would

commend him as he staggered away," Janda said. "The next thing we knew, we were

seeing all these little children staggering around the field like little

Muhammed Alis. When we asked the children afterward what they liked most and

least about soccer practice, they would always say they disliked the heading

drill the most. They said after the drill they felt dizzy, or heard ringing in

their ears, or saw two of everything, or they felt like they would throw up.

Actually, these are all signs of a mild concussion."

At risk for brain damage?

Janda and his crew are conducting a longitudinal study of

soccer players ages 11 - 13 in Ann Arbor to determine if several years' worth of

heading a soccer ball in practice and competition has an effect on their

information processing abilities. Janda's project is inspired by a Norwegian

study conducted a few years ago of soccer players ages 19 and older who played

soccer throughout their school-age and adolescent years. The researchers there

reported that 85Wo of those studied demonstrated permanent information

processing and memory deficits.

"Most coaches we've approached about this lean toward

tradition, and are not enthusiastic about having their players wear helmets,

especially during the games," he said. "Many of them feel their players will be

'wimps,' or they won't learn how to head the ball properly. But by wearing the

helmets at least during practice, or using soccer balls with less air during the

heading exercises, the players might not leave practice with the kinds of

concussive symptoms we've been seeing."

A busy agenda

The institute is also busy pursuing safety product evaluations

and research in a number of other areas, including:

· alternative coaching techniques in

football;

· the development and testing of a

different type of cleated structure to reduce foot, ankle and knee injuries in

football;

· a study of non-lethal projectiles

used at sporting events for crowd control;

· a surveillance study assessing the

prevalence and severity of recreational basketball injuries;

· the prevention of cervical spine

injuries in hockey; and

· studies of shin guards and their

protective capabilities in soccer

Proposed projects include the development of future

protective head gear for football and biking, improved surfaces for running, and

a shoulder injury prevention program.

As part of the institute's advocacy efforts, the Advisory

Council will continue to extend the research findings of the institute to the

public. Advisory Council members include leaders from amateur and professional

sports-including notables like John Unitas, Oscar Robertson, Walter Payton and

Bonnie Blair-as well as community and business leaders who lend their expertise

on sports and health care cost-related issues.

Gaining recognition

Janda said the institute's efforts are slowly gaining

recognition throughout the world, and the institute has already assisted the

House Subcommittee on Commerce, Consumer Protections and Competitiveness in its

investigations of the ethical practices of manufacturers marketing sporting

goods alleged to be safer Likewise, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

developed a position statement advocating the widespread use of breakaway bases,

predicated on Janda's research findings.

Janda has presented his research to the American

Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society, the American College of Sports Medicine, the

Canadian Academy of Sports Medicine, and the National Athletic Trainers

Association. He also presented his findings to the French government, and he

will be the keynote speaker on sports injury prevention at a meeting this

November hosted by the Australian government and the Sydney Olympic Organizing

Committee.

"We all tend to think of sports injuries as being little

bumps and bruises, and not having significant ramifications," he said. "But the

medical and job-related costs that add up when someone misses work for several

weeks and has to have surgery and rehabilitation can be very significant. Some

of these athletes may never be the same after their injury, and that's what we

want to avoid."

|